Lisbon, Portugal

Even before arriving, I knew I would love Lisbon. From what I’d read and the pictures I’d seen, it seemed like such a colorful and vibrant place. Plus, there have been many parallels drawn between Lisbon and San Francisco – my favorite U.S. city – like the undulating hills with beautiful views, the distinctive neighborhoods, each with its own unique character, and, of course, the big red suspension bridge crossing the bay (or the river, in Lisbon). So, after spending a few days and nights there in April of 2024, I wasn’t at all surprised by how taken I was with Olissippo, the Phoenician name for Lisbon, meaning “enchanting port” – a well-deserved title.

For Charles and me, a memorable travel experience begins with a noteworthy hotel. Upon arriving in the city, we checked into Palácio Ludovice, where we had an exceptional stay. Perhaps even more exceptional is the palace’s history. It was built in the early 1700s as the private residence of João Federico Ludovice, the architect to King João V, one of Portugal’s most heralded monarchs. Lisbon was struck by a devastating earthquake in 1755, which leveled most of the city, but remarkably, the palace survived. The building’s robust structure inspired the reconstruction of Lisbon to seismic norms, led by Ludovice himself. In more recent times, the palace has been fully renovated and converted into a boutique luxury hotel, preserving the historic character of many elements like the majestic staircase, decorated pilasters, stone window frames, 18th-century blue-and-white tiles, and chapel with Masonic symbols and Hebraic inscriptions.

We stayed in a Grand Deluxe room, which was spacious and bright, with several large windows overlooking Miradouro de São Pedro de Alcântara – Lisbon’s most iconic observation point offering a panorama of the city. Our room featured modern walnut furniture, luxury linens, and flourishes of colorful embroidery. A separate dressing area was replete with built-in cupboards, and the large bathroom had his-and-his sinks, a free-standing tub and separate shower, Caudalie bath products, and wainscotting made of hand-painted blue tiles. Breakfast was an elegant affair, served in the soaring and verdant courtyard of Federico, the hotel restaurant. Each morning, a plethora of fresh fruit and delectable baked goods were beautifully displayed on the oval bar. Upon returning to our room at the end of each afternoon, an edible treat was waiting for us, like a bottle of port or a plate of pasteis de nata, the renowned Portuguese mini custard tarts. The prime location adds to the hotel’s splendor. Situated at the intersection of the Chiado, Bairro Alto, and Príncipe Real neighborhoods, many charming shops and some of the city’s most coveted restaurants are only a few minutes away on foot. We truly loved our stay at Palácio Ludovice and highly recommend it to anyone visiting Lisbon.

Upon our first full day in the city, I had the hotel arrange a private half-day tour. Our guide, Carolina, met us in the lobby at 11, where we set out to the nearby Miradouro de São Pedro de Alcântara to get a lay of the land. From this prime lookout, you can see a wide expanse of Lisbon, including the tree-lined Avenida da Liberdade, the Baixa district, the Sé, Castelo de São Jorge, and the colorful homes ascending the Alfama hill. It was a beautiful spring morning, and Lisbon was on display in all her glory. Next to the miradouro is the historic Elevador da Glória funicular, which connects the top of Bairro Alto with the Rossio, the city’s main square. We skipped the ride, however, and slowly hoofed our way down the hill, stopping at several key sites along the way.

Located a few blocks from the miradouro is the Church of São Roque, the first Jesuit church built in Portugal, and like Palácio Ludovice, it survived the earthquake of 1755. Carolina led us inside and began to describe the church’s interior, a stunning example of Baroque architecture, with richly decorated chapels, vibrant and intricate azulejo tiles, sculptures, and paintings. Many of the tiles date back to the late 16th century and are considered some of the finest examples of Portuguese tile art from that period.

We then walked over to the Chapel of St. John the Baptist, mid-nave, which is another Baroque treasure with a fascinating history. It was commissioned by João V in 1742 to two Italian artists, Luigi Vanvitelli and Nicola Salvi, and designed and built in Rome over the next five years. The chapel was then dismantled in 1749 and dispatched to Lisbon in three ships. Upon arrival two years later, its reassemblage was overseen by none other than João Federico Ludovice, Portugal’s royal architect. The chapel is one of the most sumptuous and opulent in all of Europe, and, at the time, was the most expensive ever built. It features three figurative mosaic panels that look painted at first glance, along with columns, carvings, and decorations made with some of the most costly materials like agate, lapis lazuli, and of course, gold leaf. It is quite the showstopper piece, and with an ironic twist – João V would never lay eyes on his lavish creation; he died in 1750, before it arrived in Lisbon from Rome.

From the church, we continued downhill to Rua Garrett, an historic pedestrianized street that played an important role in Lisbon’s commercial and cultural history. In the 19th century, it was home to many theaters, cafes, and bookstores – some of which are still alive today, like the iconic Café A Brasileira and Livraria Bertrand, one of the oldest bookstores in the world. All throughout Lisbon, streets and sidewalks are constructed with carefully laid stone tiles known as calçada portuguesa, or Portuguese pavement, and Rua Garrett is no exception, featuring an intricate black-and-white diamond pattern.

Carolina then led us slightly uphill to Largo do Carmo, one of Portugal’s most significant squares. It takes its name from the Gothic-style Carmo Convent, which was mostly destroyed in the 1755 earthquake, with only the roofless nave remaining. The square was the site of the Carnation Revolution, a peaceful coup d’état that took place on April 25, 1974. It marked the end of the Salazar’s Estado Novo regime, a dictatorship that had ruled Portugal since 1933. The revolution was named after the carnation flowers that soldiers wore in their gun barrels as a symbol of peace. This significant event led to the country’s transition to democracy and the end of colonial rule. We were visiting only a few weeks shy of the 50th commemoration of the revolution.

We popped around the corner from Largo do Carmo to see the upper platform of the Neo-Gothic Elevador de Santa Justa. This 148-foot tall cast iron structure was designed in the early 20th century by Raoul Mesnier du Ponsard, a disciple of Gustave Eiffel, to connect the Baixa neighborhood with Bairro Alto. The observation deck at the top offers an amazing view of the city center. At the time, I was reading David Leavitt’s biographical novel, The Two Hotel Francforts, about two couples who meet in Lisbon in 1940 as they wait to leave a war ravaged Europe on a ship sailing for New York. In one of those fateful moments, I mentioned the book to Carolina on the observation deck, and she told me to look down on the street below, where, in calçada portuguesa, Hotel Francfort was spelled out in the sidewalk, two blocks from the base of the elevator. Sadly, the building was shuttered, but nonetheless, it made me feel closer to the characters in the book.

Back from Largo do Carmo, we made our final leg of the descent down to Praça Dom Pedro IV, or more commonly referred to as the Rossio. This historic square is located in the heart of Lisbon, and over the course of several centuries, has been the setting for numerous demonstrations, executions, and celebrations. It is surrounded by bars and restaurants, making it a popular gathering place for Lisboans and visitors alike. The entire square is covered in a repeating mosaic of wave-patterned calçada, which pays homage to Portugal’s maritime history. When you stare hard enough, the tiles create an illusion of waves rippling over the sea.

Carolina led us to Largo de São Domingos, a small adjacent square to the Rossio. I had asked her to share with us some Jewish history of Lisbon. At the center of the square is a memorial dedicated to the victims of the 1506 massacre, during which thousands of Jewish Cristãos-Novos, “New Christians” who were forced to convert to Catholicism, were attacked and killed all throughout the city. The massacre began in the Church of São Domingos, located in front of the square. The memorial was inaugurated as part of the 500th anniversary of the event. As sad as this story is, what’s even sadder is how immune I’ve become to the tragedies of my people and culture.

Our tour ended on a sweet note at A Ginjinha, Lisbon’s oldest ginjinha bar. Also located on Largo de São Domingos, this historic establishment opened its doors in 1840, serving the iconic Portuguese sour cherry brandy. The bar is literally a hole in the wall. You walk up to a counter, and after putting down three euros, the bartender pours a shot glass to the brim with the red syrupy elixir. You then take your shot glass and step into the square, where you sip your ginjinha casually; throwing it back in one gulp is frowned upon. When you’re done, you return the glass to the counter, wash your hands in the sink next to the bar, and then go on your merry way. According to Carolina, this tradition is shared by Lisboans all throughout the day, all across the city.

Later that day, Charles and I ventured out to Lisbon’s historic riverfront district of Belém, which was the departure point for many of Portugal’s most famous explorers, including Vasco da Gama. Here, we visited one of Lisbon’s most iconic sites, the Belém Tower, built between 1514 and 1520 during the height of the Portuguese Renaissance to protect the city from raids along the Tagus. It is a shining example of Manueline architecture style, a Gothic-influenced style known for its intricate ornamentation with nautical and exotic themes that highlight Portugal’s maritime power during this era. We arrived during low tide, which enabled us to get closer to the tower’s exterior and examine the stunning details that prevail on just about every surface.

Another shining example of Manueline architecture is the Jerónimos Monastery, a UNESCO World Heritage Site located a few yards away from the tower. This masterpiece was commissioned by Manuel I to commemorate Vasco de Gama’s successful voyage to India – the first European to reach India by sea. Construction began in 1501 and took 100 years to complete. There was a long line for tickets, but I was able to purchase a pair on my phone in real-time. We decided to skip the church and headed directly to the cloisters, which were both stunning and serene. Built using gold-colored limestone from Sicily, the intricate stone carvings and ornamental arches are works of art in their own right, made even more beautiful when illuminated by the sun’s reflection.

Near the tower and monastery along the riverfront, we stopped to survey the Padrão dos Descobrimentos, the Monument to the Discoveries, a newer symbol of Portugal’s maritime heritage. First built in 1940 as a temporary structure for the Portuguese World Exhibition, it was reconstructed in 1960 as the 171-foot-tall hulking structure of stone and concrete we see today. The monument looks as though it’s about to set sail with a super crew of historical figures from Portugal’s Age of Discovery, including Henry the Navigator, Vasco da Gama, and Pedro Álvares Cabral. You can tell how proud the Portuguese are of their maritime history. The monument was gleaming, as if it were recently scrubbed down and polished, like a piece of sculpture displayed on an etagere.

The next day, we ventured to the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, a non-profit established in 1956 to manage the vast art collection of the namesake Armenian oil tycoon, who was one of the wealthiest men of the early 20th century. Gulbenkian moved to Portugal in 1946 to escape political instability and turmoil in the Middle East. Salazar, Portugal’s infamous dictator at the time, welcomed Gulbenkian (and his deep pockets) with open arms, but with one exception – he would need to contribute to the promotion of Portuguese culture and international prestige. This quid pro quo led to the creation of the foundation, which has benefitted the Portuguese ever since. In addition to the museum, the foundation operates a number of other cultural and educational institutions, including a music center, a theater, and a library; and is involved in various philanthropic activities, such as supporting education, healthcare, and social welfare programs.

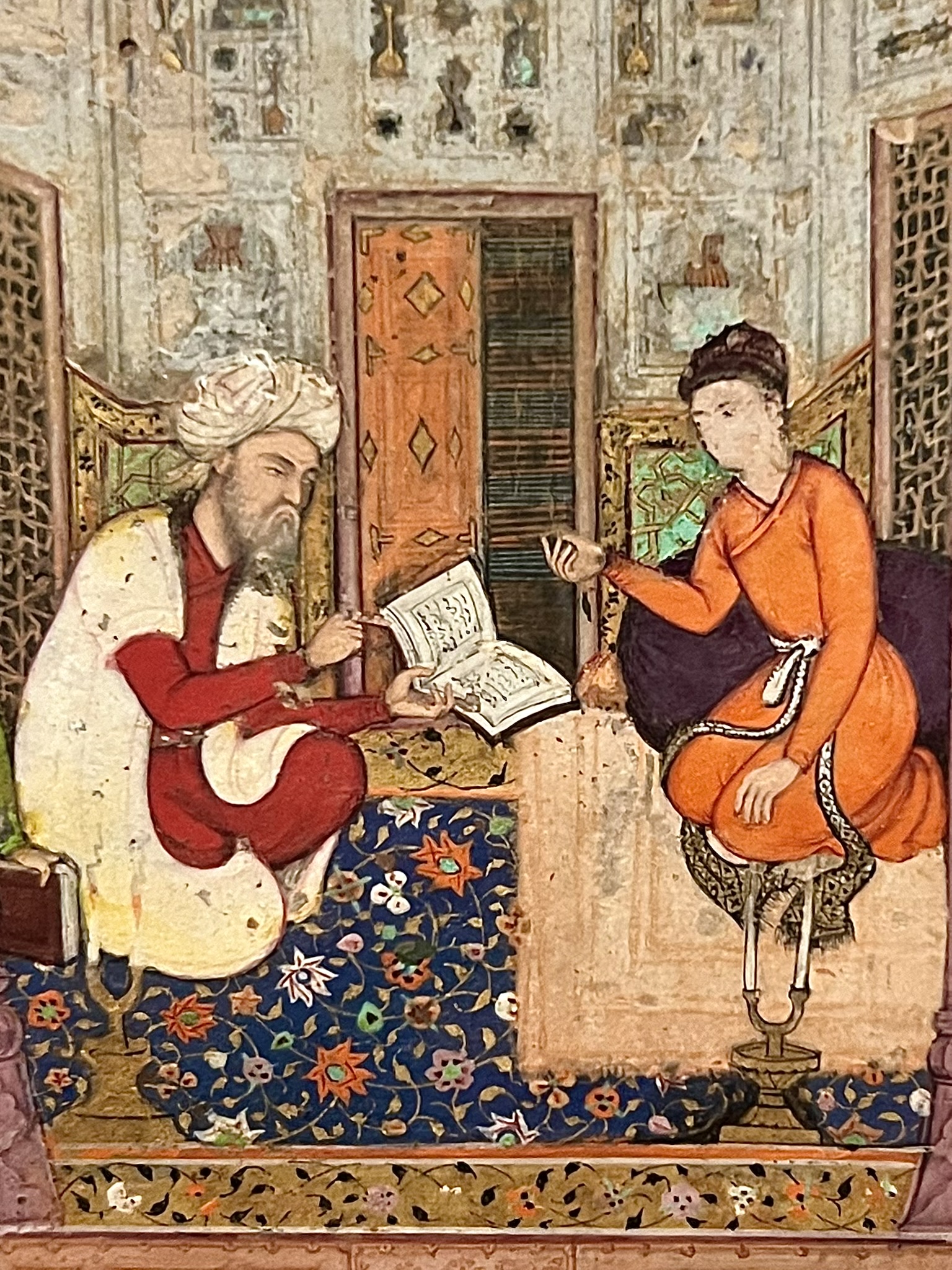

The foundation is located in a lush garden, on the site of Gulbenkian’s former villa. The Centro de Arte Moderna Gulbenkian was closed for renovations, so we spent most of our time at the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, which houses the permanent collection of diverse art and artifacts from around the world. On display is a vast array of ancient art, including Egyptian antiquities, Greek and Roman sculptures and pottery, Chinese porcelain and jade, Japanese prints, and relics from Mesopotamia and Persia. I was awe-struck by a cabinet of Mamluk gilded and enameled glass lamps from the 14th century. Each looked like a genie was hidden inside, waiting to be released with a gentle rub.

There are several galleries dedicated to Western paintings, which range from Italian and Dutch Renaissance masters to 20th century modern and contemporary art. I was drawn to two paintings by Francesco Guardi from the 18th century, each depicting vibrant scenes of Venetian life. They are in the same vein as Canaletto, but not as exacting, with looser brushwork. I was also intrigued by Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret’s Les Bretonnes au Pardon, a large-scale realist painting from 1887 featuring a group of Breton women in traditional costumes partaking in a religious pilgrimage. At the center of the painting is one young woman staring at the spectator, her melancholy expression exuding an intense solitude. She held my gaze for several minutes and wouldn’t let go.

For Charles and me, the real showstopper was the final gallery, which displays Gulbenkian’s renowned collection of Lalique. Gulbenkian was a dedicated collector of René Lalique’s work and played a significant role in supporting his career. Protected by a maze of glass cases, numerous pieces by the prominent French Art Nouveau designer are showcased as eye candy, from exquisite pieces of jewelry to stunning objets and decorative arts. I have too many favorites to mention, but a few callouts include a Dragonfly-woman corsage ornament made of gold, diamonds, semi-precious stones, and enamel; a Female face pendant framed with sapphires, diamonds, and luscious blue and teal enamel; and an incredibly intricate Nymph in a tree pendant carved in ivory and framed by sapphires and diamonds. Upon exiting the gallery, we were giddy with excitement by the amount of beauty we had just taken in.

On our last day in Lisbon, the hotel arranged a private tour of Sintra, a UNESCO Cultural Landscape just west of Lisbon, known for its scenic beauty and hilltop palaces. There’s too much to include here, so you’ll have to jump over to my dedicated Sintra post to read more.

As a self-proclaimed shopaholic, Lisbon is a dangerous place to spend free time with a credit card. On our first afternoon, we visited EmbaiXada, a boutique shopping gallery very near our hotel in the trendy Príncipe Real district. It’s located in the 20th century neo-moorish Ribeiro da Cunha Palace, with the traditional central patio converted into a restaurant, cafe, and bar. Inside, I purchased a cobalt blue long-sleeve knit button down from A Indústria, a Portuguese menswear company, and two simple yet beautifully cut wovens from ISTO, another Portuguese brand known for its high quality everyday basics. Charles and I also purchased two soft herringbone weave woolen blankets from Ecolã, a family-owned mill established in 1925.

Across the street from our hotel was another well-curated men’s store, Refém, which carries tops, bottoms, shoes, and accessories from contemporary Portuguese and Spanish brands. After scoping out the scene, I brought Charles back, where we both partook in mini makeovers. Diagonal from Refém is Claus Porto, the renowned Portuguese soap and fragrance institution first established in 1887. I honed in on several exquisite smelling and looking bars of soaps, but I waited to visit the flagship location in Porto before purchasing. I had read about Loja da Burel, the factory store of the celebrated Portuguese brand that produces wool homegoods and fashion with looms from the 19th century. The fabrics all throughout the store were beautifully textured and rich in color. We wanted to purchase some new throw pillows, but they were out of stock in the sizes we wanted. Fortunately, the Porto location came through.

I would be remiss not to mention some of the great meals we had. On our first afternoon, we had lunch at Tapisco, a tapas and petiscos bar from Henrique Sá Pessoa, one of Portugal’s most celebrated chefs. It was conveniently located in Príncipe Real, just around the corner from the hotel. The space was long and skinny, with a parallel red banquet and stone bar running the full length of the dining room. We ordered several mouth-watering small plates like octopus salad, cuttlefish tempura (Portugal’s version of fried calamari), and tortilla de patata. The dishes were traditional in nature but prepared with a contemporary perspective. It was the perfect first meal to kick off our Portuguese adventure.

In celebration of my 40th birthday, one evening we dined at Belcanto, the two Michelin star crowning jewel of chef José Avillez’s culinary empire. We had an unforgettable meal, featuring nine courses inspired by Avillez’s memories and experiences. Several minutes before each tasting was served, a small card was placed in front of us. Each card highlighted the dish we were about to eat with an illustration of key ingredients along with several words used by the chef to draw his inspiration. I loved this concept. I often find at fine dining establishments that you’re all-too-quickly explained the components of a dish, and then you forget what you’re actually eating. I was referencing these cards all throughout the meal.

A particular standout was one of Avillez’s signature dishes, “The garden of the goose that laid the golden eggs.” This gastronomic play on the classic fable was composed of an egg, cooked at a low temperature and covered in gold leaf, sitting on a bed of crispy bread and mushrooms. The result is a radical conglomeration of textures and flavors. I also swooned for the crispy and juicy suckling pig served with fried trotter packets in an umami-rich orange peel puree. For the dessert courses, our napkins were taken away and replaced with a dessert sleeve – a white linen cuff that fit over our shirtsleeves. We were explicitly told to wipe our mouths on our sleeves, to mimic Avillez’s preferred method of cleaning his face as a child. This was such a sweet and whimsical touch. And the sleeve came in handy! The first dessert was a play on choco, cuttlefish, and had lots of gooey chocolate bits to mimic squid ink. In honor of my birthday, I was presented with a large candle, which was actually a cake with a white chocolate shell and “wax” drippings, to boot. As a parting gift, Charles and I were each presented with all the cards from our meal, tucked away in an envelope and stamped with a classic red seal. As I write this paragraph, I’m reliving the memories of our meal through those handy cards.

Last visited in April, 2024