Jewish Quarter, Budapest, Hungary

I learned so much from Andrea Medgyesi, our guide from the Jewish Visitors’ Service of Budapest. She conducted an incredibly informative, contemplative, and thoughtful tour of the Jewish Quarter. A descendant of Holocaust survivors, Andrea provides a unique point of view as a local woman carrying the torch of Jewish history, culture, and religion from post-World War II through Hungary’s age of Communism and to the present day. Any Jewish person visiting Budapest should be required to take Andrea’s tour.

Before I share stories and anecdotes from the tour, I’d like to detail some important facts I learned about Jewry in Budapest from Andrea:

The original Jewish Quarter of Budapest arose in Buda and thrived during the Ottoman reign; it was home to Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Syrian Jews.

During the Habsburg rule, Queen Maria Theresa expelled Jews from Buda. After which, Jews began to settle across the Danube in Pest in the Erzsébetváros district, which grew into one of the largest Jewish communities in the world before the Holocaust.

At the turn of the last century, Jews represented 23% of the total population of Budapest, which earned the city the nickname, Judapest.

Hungary’s Jewish population before World War II: 825,000; the number of Hungarian Jews that perished in the Holocaust: 565,000.

We met Andrea in front of the Jewish Community Center on Dob utca 35, right in the heart of the Jewish Quarter. Along the way we passed what another guide referred to as the beautiful ruins of Pest—grand revival-style buildings, many crumbling or in disarray from neglect during the Communist era. Andrea was prompt and ready to roll. She took us inside the community building for a crash course on the history of Jewry in Budapest.

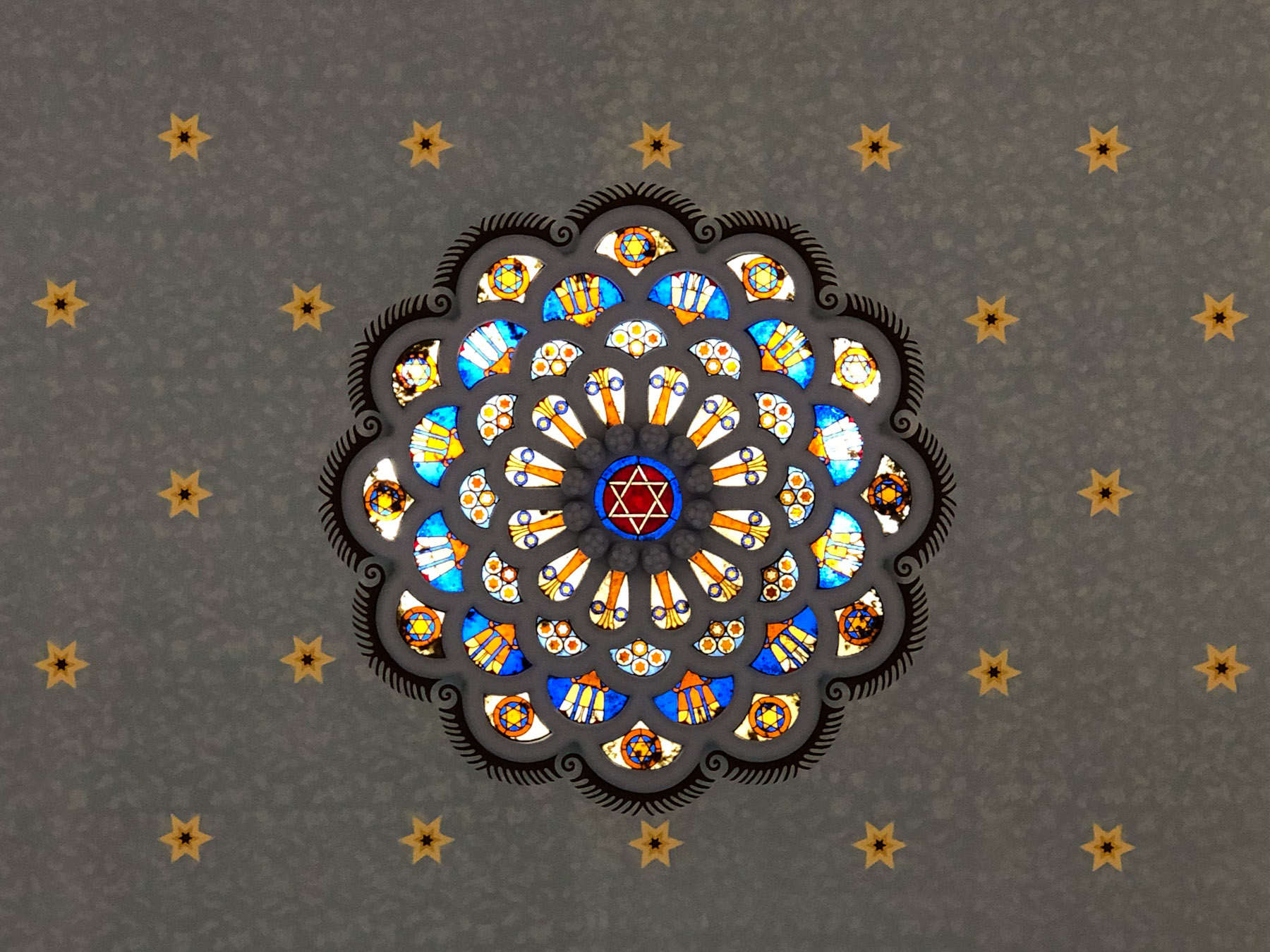

From there, we walked around the corner to Kazinczy utcai to the eponymous Kazinczy Street Synagogue, an orthodox shul constructed in 1912 with a Viennese Art Nouveau-influenced design. Everything from the chandeliers to the hand-painted columns and rafters added to the awe-inspiring experience upon walking into the grandiose main sanctuary. The walls are painted a beautiful cornflower blue with gold accents. The ceiling is inlaid with several rose stone-style stained glass florets designed by Hungarian mosaicist Miksa Róth. To this day, the Kazinczy Street Synagogue serves as a mainstay for the Budapest orthodox community, housing a kindergarten, a Talmud school, a kosher butcher, and a mikveh.

Next, Andrea brought us to Szimpla Kert, the original ruin bar in the Jewish Quarter, just down the street from the Kazinczy Street Synagogue. What is a ruin bar, you may ask? After the Iron Curtain was lifted in 1989, many of the buildings in the Jewish Quarter were abandoned and in a state of decay. In the early 2000s, a group of young locals rented a dilapidated house and converted it into a summer bar, which attracted other young locals and sparked the dawning of a new era in Hungarian nightlife. Today there are a plethora of ruin bars all over the city, but Szimpla is where it all began.

Coming from an opulent orthodox synagogue, the juxtaposition was quite drastic. The walls all throughout Szimpla Kert are covered in hazarai, an appropriately yiddish word for “junk,” and much of the original exposed brick has the appearance of decrepitude. A key reason why there was so much decay in the Jewish Quarter was because so many of its inhabitants were killed in the Holocaust. Upon the Soviet occupation post-World War II, the district remained poor and neglected. Even today, over 30 years after the lifting of the Iron Curtain, many of the buildings are still in shambles. Despite the district’s popularity, the ruins remain because they are what attract the masses.

Next stop: Café Noé Cukrászda, a kosher bakery that specializes in flódni, a traditional Hungarian Jewish semi-sweet cake. Flódni consists of layers of poppy seed, apple filling, walnut paste, and plum jam separated by thin layers of dough. Originally a popular treat for Eastern-European Jewish families during high holidays, today it can be enjoyed any time of year at numerous bakeries throughout the Jewish Quarter. Of course we had to try a piece…and loved it. The taste reminded me of rugelach.

Andrea then led us past the Rumbach Street Synagogue, another architectural star in the Jewish Quarter. The Moorish Revival design was imagined by Austrian architect Otto Wagner, a father of the Vienna Secession movement, and completed in 1872. Wagner adopted elements of Islamic style, like the eight-sided domed sanctuary with intricately patterned interiors and the pair of minarets hovering above the entrance. The synagogue is inactive and closed to visitors, but after years of neglect, it is currently under restoration and will once again serve the Jewish community for religious observance and also act as a cultural center.

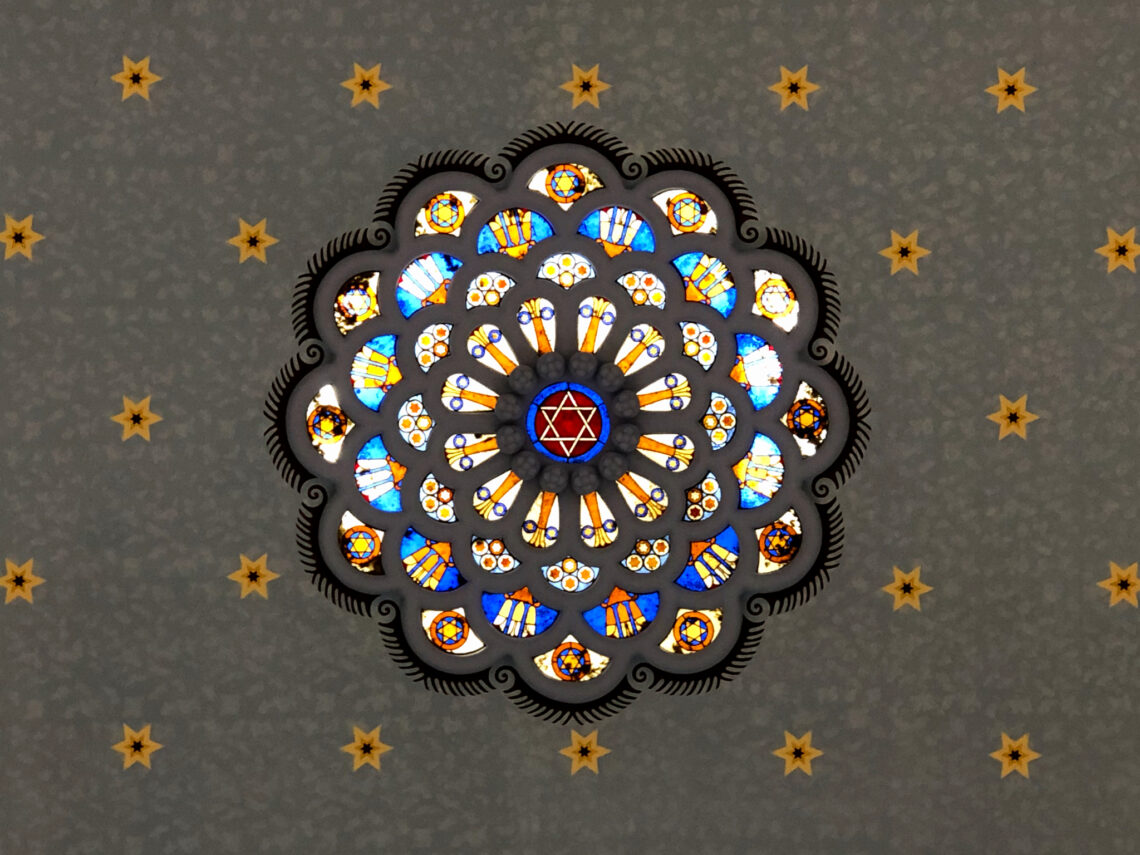

Two blocks away stands the pièce de résistance of Budapest shuls—the Dohány Street Synagogue. Designed by another Austrian architect, Ludwig Förster, in the Moorish Revival style and completed in 1859, the synagogue still serves the Hungarian Jewish community today and, depending on who you ask, is either the second or third largest synagogue in the world. Two onion domes and a stained glass rose window tower over the main entrance. The interiors are cathedral-like with three aisles, an upper gallery (where women are required to sit during services), and a 5,000-pipe organ—a rarity for a synagogue. There is also a cemetery in the side yard, another rarity. The cemetery, however, was not a part of the original design. It came about as a result of the starvation and suffering of the Jews in the Jewish Ghetto during WWII, 2,000 of whom died and were subsequently buried in the courtyard of the synagogue.

Upon entering the main sanctuary, Charles and I were required to put on paper kippehs. I was actually so enamored with the fresco-adorned ceilings that a guard practically accosted me for not noticing the kippeh requisite. The frescoes were done in warm jewel tones and hand-painted by Frigyes Feszl, a son of the Hungarian romantic movement. We continued through a side door of the sanctuary and past the cemetery, a very somber site some 75 years after the war.

The rear courtyard of the synagogue is home to the Raoul Wallenberg Holocaust Memorial Park. In 1987, actor Tony Curtis established the Emanuel Foundation in memory of his father, Emanuel Schwartz, a Jew who emigrated to New York from Hungary. The foundation commissioned and donated a sculpture to commemorate the 565,000 Hungarian Jews who perished in the Holocaust. The sculpture, entitled Memorial of the Hungarian Jewish Martyrs and made by Hungarian artist Imre Varga, features a weeping willow whose leaves bear inscriptions with the names of Holocaust victims.

Connected to the synagogue is the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives, built on the site of Theodor Herzl’s childhood home. Theodor Herzl was the father of the Zionist Movement, which promoted Jewish immigration to Palestine in an effort to form a protected state for the Jewish people. Hundreds of Hungarian Jews fled to Palestine in advance of the pro-Nazi attacks. Today, many of these same families are breathing new life into the Jewish Quarter. A prime example is the Gozsdu Udvar, a courtyard we walked through en route to our next stop, the Glass House. The Gozsdu Udvar opened in 1902, connecting seven buildings and six interconnecting passageways. Like much of the Jewish Quarter, it fell into disrepair until recently, when an Israeli developer swooped in and converted it into a hip food yard with restaurants and bars plus a flea market on weekends.

The Glass House Memorial Museum is a 20-minute walk from the Jewish Quarter, located in the Lipótváros district of Pest. The memorial honors the valiant and heroic Swiss diplomat, Carl Lutz, who is credited with saving the lives of over 60,000 Hungarian Jews during the pro-Nazi invasion of 1944. The museum is housed in a room of an old glass factory that was put under the protection of the Swiss Embassy during the war. It was in this same room that Carl Lutz, acting on behalf of 12 countries who closed their consulate offices, issued letters of protection and safe conduct documents, which enabled thousands of Jews safe passage out of Hungary. More than 3,000 Jews also sought refuge in the glass factory itself. The building was liberated on January 18, 1945, and almost everyone who took refuge here survived.

After the Glass House, we followed Andrea to the final stop on the day’s tour: a very controversial monument erected in 2014 in Szabadság Square to honor “all the victims” of the Nazi occupation of Germany 70 years earlier. Why so controversial? Many believe the monument is an attempt to absolve Hungary of any wrongdoing by putting the blame entirely on Nazi Germany. Jews and non-Jews alike oppose the monument—and Prime Minister Viktor Orbán—for distorting the nation’s role in the Holocaust. What’s more, the original Hebrew inscription of the monument had mistranslated the word “victims” as “sacrificial animals”. Accident or escapade?

We bid our adieus to Andrea and made a beeline back to the Jewish Quarter to Mazel Tov, an indoor garden-like cultural space cum restaurant cum cafe serving Israeli-inspired cuisine. We worked up an appetite from all that sightseeing, and what better way to end our tour of the Jewish Quarter than with neo-Jewish fare. We ordered copious plates of hummus, sabich, and delicious fried eggplant, along with the Mazel Tov pastrami sandwich, which was out of this world. It was a typical Jewish way to end the day—first we nourished our minds and our senses…and then our tummies.

If you find yourself in Budapest, I highly recommend booking a tour with Andrea. You can find out more by visiting: http://jewishvisitorsservice.com/

Last visited in September, 2019