The Alhambra, Granada, Spain

Every trip has its favorite moment. On a recent vacation to Spain, mine was the afternoon Charles and I spent in Granada touring the Alhambra.

The day began in Málaga, our base for four nights, where we got an earlyish start to make the 80-mile journey to Granada in our rental car. We took the coastal route along the A-7, Spain’s meticulously maintained Mediterranean corniche. It was a gorgeous spring day, with a cloudless sky and a beaming sun blanketing its radiance across the vast expanse of cobalt sea. Just past Almuñécar we exited onto the A-44, which traverses the mighty Sierra Nevada mountains (the highest in Spain!) to reach Granada. After many twists and turns around hulking, schist-exposed foothills, the higher peaks of the range appeared off to our right, still snow-covered in May – and living up to their namesake (Sierra Nevada means “snowy mountains” in Spanish).

Upon descending the A-44, the roadway merged onto the GR-30, and the vega, or plains, of Granada unfurled before us. I could make out the Alhambra garrison on a distant hilltop. We passed through the Puerto del Suspiro del Moro. This is the supposed mountain gap where Boabdil, the final Nasrid ruler of the Emirate of Granada, looked back on the city and wept as he mounted his journey in exile after surrendering the last Andalusian caliphate to Isabella I and Ferdinand II in 1492 (more on that later).

Finally we arrived in the city with a few hours to spare before our private tour of the Alhambra. Just by walking the streets of Granada, I could sense a magical aura and magnetism in the air. We strolled through Plaza Nueva and Plaza de Santa Ana, two beautiful adjacent squares bubbling with fountains and surrounded by gleaming Spanish Renaissance palaces in various hues of siena and umber. We then traipsed along the Carrera del Darro, an ancient road that runs parallel to the Darro ravine at the base of the fortress mount. We delightfully stumbled upon Patio de los Perfumes, a fragrance atelier that draws its inspiration from Granada and its environs. I often look for unique fragrances during my travels to remind me of the places I visit. Needless to say, I wasted very little time purchasing an exclusive eau de parfum that blends green citrus with jasmine, vanilla, and tobacco. Every time I wear it, I’m reminded of that magical city.

Next, Charles and I climbed the narrow passageways of the Albaicín, the ancient Arab quarter that spans the hill opposite the Alhambra, high above the Darro ravine. This area received UNESCO World Heritage status in 1994 as an extension of the nearby Alhambra. We scaled several inclined alleys and stairwells to reach Mirador Placeta de Carvajales, a lookout halfway up the hill with commanding views of the Alhambra sandwiched between profuse sprays of bougainvillea cascading down the plaza walls. We continued our ascent to El Mirador de Tato, a lovely open-aired restaurant on Placeta Álamo del Marqués, with unobstructed views of the rooftops and steeples of central Granada. Beneath a canopy of umbrellas, we enjoyed a delicious lunch – some of the best croquetas de jamon on the whole trip and an arugula salad overflowing with burrata and locally grown tomatoes that were literally bursting with flavor.

Rested and sated, Charles and I carefully descended the Albaicín and made our way back to the car. The tour was to start at 3pm, and we had less than 15 minutes to drive up to the Alhambra, repark, and meet our guide. Suddenly things turned stressful: Google Maps kept rerouting us in the wrong direction, and we couldn’t figure out how to exit the city center. We must’ve been visibly distressed because a good samaritan (so we thought) on a motorcycle asked us where we were going, and had us follow him around several hairpin turns through a residential neighborhood that connected with the Alhambra parking area. We pulled over to thank him with a €10 tip — which he thought wasn’t enough. So we doubled it and proceeded on to the parking area, chuckling that we were officially “those Americans” that got lost in Granada and were swindled by a local.

Through GetYourGuide, I booked a three-hour private tour of the entire Alhambra complex, including the Generalife palace and gardens, the Alcazaba fortress, and the Nasrid Palaces. Our guide, a young Polish woman named Gosia, arranged all the tickets in advance and met us promptly at 3 in front of the main entrance. I specifically booked a late afternoon tour, knowing that larger groups tend to start earlier in the day. There were still a lot of people, but the crowds were manageable and thinned out as the afternoon progressed.

Like all of our previous guides on the trip, Gosia began with a brief history of Andalusia, recounting the various conquests and annexations from the Romans to the Visigoths to, of course, the Arabs. Between 711 and 1492, there were numerous emirates and caliphates throughout Al-Andalus (Arabic for Andalusia), where Muslims, Christians, and Jews often lived in unity. What makes the Alhambra so special is that it was the seat of the last Muslim stronghold, ruled by the Nasrid dynasty, which eventually fell to the hands of the Catholic monarchs, Isabella I and Ferdinand II.

Gosia first led us to the Generalife, the summer palace and gardens of the royal family. Perched on the Cerro del Sol (Hill of the Sun), the Generalife looks across a dell to the Alcazaba and Nasrid Palaces. Growing in the dell are terraced vegetable gardens and orchards that have been tended to for centuries. Gosia informed us that the produce is donated to the city’s less fortunate. The formal gardens are located on an upper terrace and feature a Moorish-inspired design, with ancient cypress hedges shaped into walls separating the various parterres. As an avid gardener, I was immediately taken with the bounteous floral beds surrounding me. Some were more orderly, with trained rose bushes, water basins, and gurgling fountains. Others were untamed and teeming with red poppies, orange marigolds, blue and white nigella, purple salvia, and hot pink rose campion. The colors were straight out of a Brueghel floral still life.

From the gardens, we entered the Palacio del Generalife through a courtyard brimming with jasmine. The palace complex was originally constructed in the 13th century by Muhammad II, the second Nasrid ruler, and altered many times over the centuries by other emirs and Christian reformers. The crowning jewel is the Patio de la Acequia, a courtyard at the center of the palace with a 160-foot-long water basin that is connected to the very elaborate chain of irrigation channels throughout the Alhambra. Numerous arc-shooting jets span the length of the basin, which is framed by low hedges of myrtle and surrounded by lush flower beds and pomegranate trees – the symbol of Granada. The west side of the patio is bordered by a promenade with 18 arches, added by Christians in the 17th century. A small chamber at the far end, the Sala Regia, has arched doorways that overlook the city below, with ornate filigree windows and beautiful plaster wall coverings with calligraphic inscriptions. Upon exiting we passed through another verdant courtyard, the Patio del Ciprés de la Sultana, named for an ancient cypress tree where Boabdil’s wife had a tryst with a knight from the Abencerrajes family, resulting in the murder of all the men in the entire tribe. Bad luck struck twice, the second in the form of lightning, that left only the lower trunk of the ancient cypress intact.

We walked up a flight of steps at the far end of the patio, and then Gosia led us to the base of another flight of steps, the Escalera del Agua. These steps are said to be the oldest in the garden and feature an exposed channel of running water built into the handrails. This water flows from a reservoir further up the hill and connects to all the other water features throughout the Alhambra, including the basin in the Patio de la Acequia. Water, Gosia explained, is a treasured element in Islamic culture and religion. The Nasrids, who were descendents of a desert-dwelling Saudi Arabian tribe, must’ve thought they struck it rich in Granada, where the snow-capped Sierra Nevadas provide ample water for the region.

We exited the Generalife through the Paseo de las Adelfas (Path of the Oleanders), which connects with the Paseo de los Cipréses, lined with 200-year-old towering cypress trees. We then entered the official citadel via Calle Real de la Alhambra. After walking past ruins of the old medina quarter, destroyed by Napoleon’s army in the early 19th century, we made our way to the Palacio de Carlos V. This unseemly pile of architecture was commissioned in the early 16th century by Charles V, king of Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor, who was enchanted by the Alhambra and wanted a permanent residence nearby to be able to enjoy it as he pleased. Carlos’ vision turned out to be a pipe dream. The Renaissance design took over 400 years to complete, and no member of Spain’s royal family would ever have a chance to live in it. Gosia led us inside for a brief look at the rather impressive two-story, open-aired circular colonnade, which is not visible from the outer square design. Today, the palace houses the Museo de Bellas Artes de Granada, which we did not have time to visit (next trip).

Across from the Palacio de Carlos V, we passed through the Puerta del Vino, one of the oldest gates of the Alhambra, dating back to the 13th century and the reign of Muhammad II. The Puerta del Vino leads to the Plaza de los Aljibes, named for the large cisterns buried beneath the square in what was a gully between the Alcazaba and the Nasrid Palaces. We followed Gosia into the Alcazaba, which she explained was painted all white at one time, in the Berber style of North Africa…and just like the pueblos blancos that dot the hillsides of Andalusia. From afar the facade looks reddish brown, but from up close you can actually make out some of the white paint remnants. The fortress is the oldest building in the Alhambra complex, dating back to Muhammed I, the premier Nasrid ruler, who constructed the ramparts in the mid-13th century atop previously existing Roman bulwarks from the 9th century.

We walked through the Plaza de Armas, the main square within the fortified walls, which served as a village for the civic population. All that remains today are ruins of foundations, but remarkably, you can still make out the rainwater irrigation system along with the hammam, communal oven, and dungeon. We then walked out onto the Torre de las Armas, which had commanding views of the entire Albaicín hillside along with the city center, its exurbs, the surrounding vega, and the most distant mountains. Gosia and I climbed to the top of the Torre de la Vela (Watch Tower), the western most defensive tower, which had even more impressive views, including of the snow-capped Sierra Nevadas.

Now it was time to tour the Palacios Nazaríes (Nasrid Palaces). Gosia saved the best for last…and cleverly set our entrance time at 5pm, when most tourists had already left for the day. The palaces are very special as they are a thriving example of Moorish architecture and craftsmanship, unlike any other in the world. Construction began during the reign of Abu l-Walid Ismail, the fifth Nasrid emir, in the early 14th century. Many of the important improvements and additions that are on display today were facilitated by Yusuf I and Muhammad V, the seventh and eight Nasrid rulers, father and son, respectively. The palaces are divided into three separate areas, each distinct in its own style and character: the Mexuar, derived from the Arabic word mashwar, meaning “place of counsel,” housed various administrative functions; the Palacio de Comares, the official residence of the emir; and the Palacio de los Leones (Palace of the Lions), which housed the private quarters and the harem.

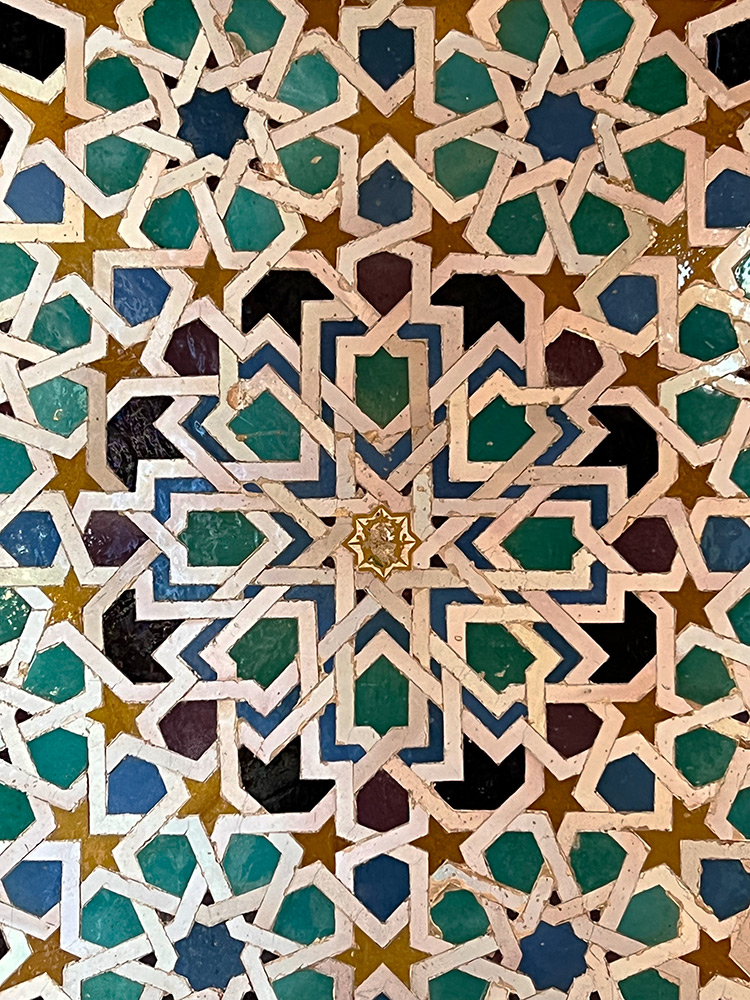

From a courtyard we entered the Sala del Mexuar, and the history of the space immediately came alive. Gosia explained that the present-day design is a mélange of Moorish and Christian influences, heavier on the latter – particularly as a result of restorations from an artillery storage shed explosion in 1590. The Arab influences are evident in the original skirting board of vivid tile mosaics and the four columns at the center of the room with archways bedecked in mocárabe corbels (honeycomb plasterwork). The tile mosaics were done in the Islamic style of zellige, which in Arabic, literally means “mosaic.” They incorporate geometric pieces of blue, green, purple, and gold tile to form bursts of stars. I was amazed by how vibrant the colors have remained after hundreds of years. Gosia pointed out the coats of arms of the Christian reformers that were placed on the center of each burst. The mocárabe corbels were molded from gypsum and feature three-dimensional, niche-like shapes, which, at one time, were painted with mineral pigments of blue, red, black, and green, and finished with metallic gold and silver. Today, the only color that remains is blue, which was derived from lapis lazuli imported from the mountains of Afghanistan.

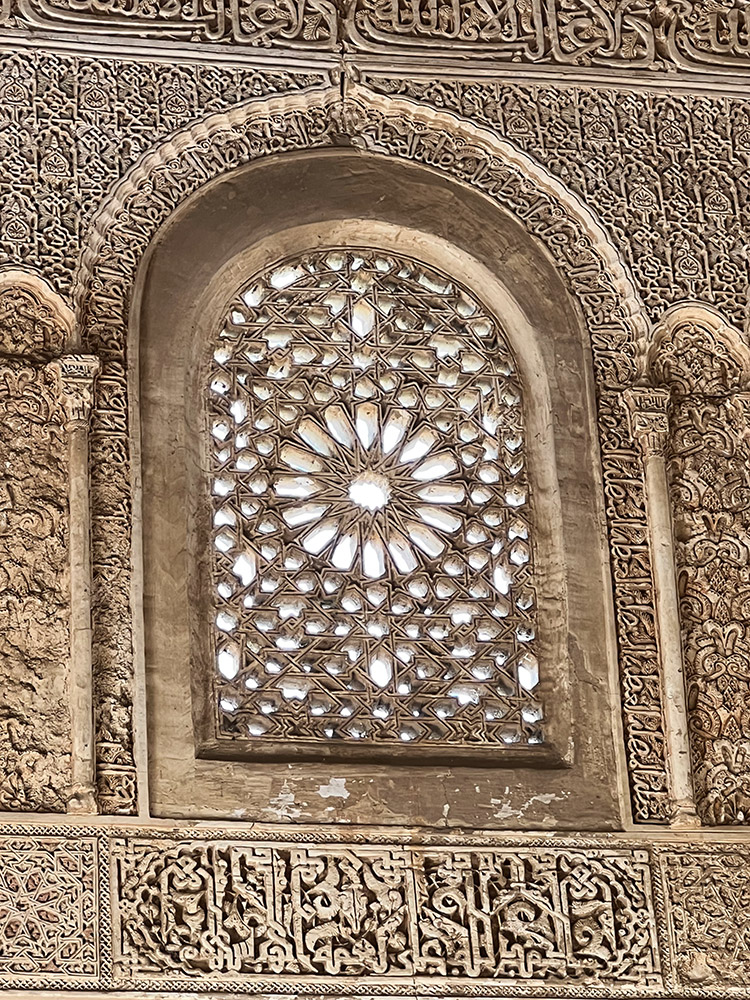

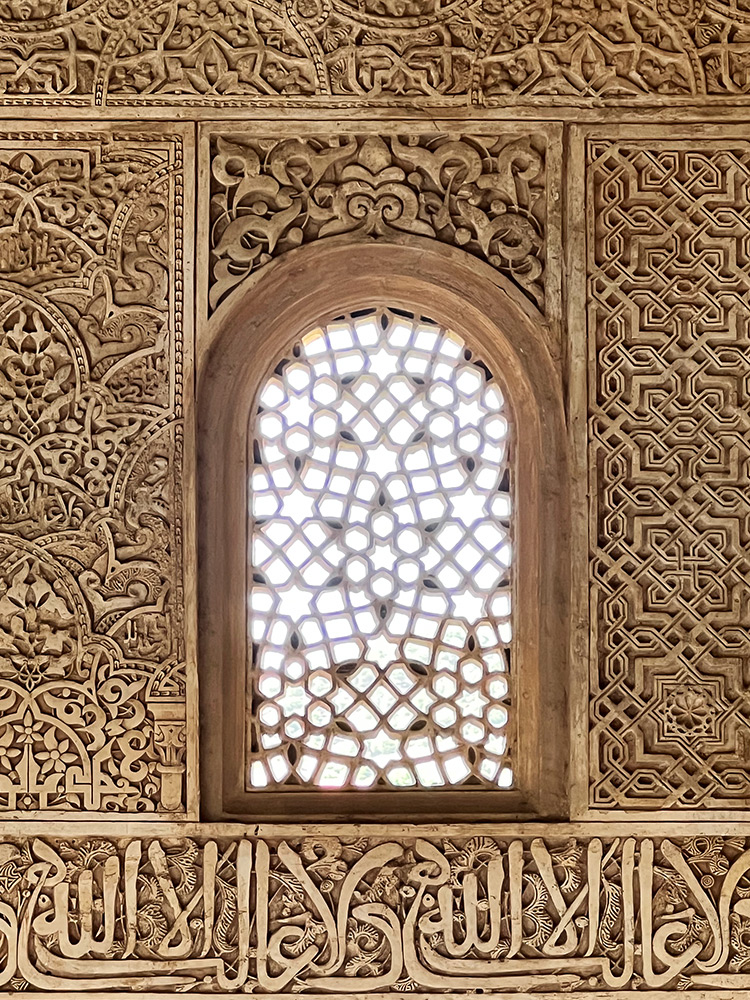

At the back of the Sala del Mexuar is a chamber with arched windows facing north towards the Albaicín, which was used by the emir for council meetings. Ornate plasterwork covers the walls. This technique was developed by Nasrid artisans in the Alhambra, combining vegetal, geometric, and calligraphic decorations in horizontal strips chiseled from gypsum. A repetitive inscription appears just above the windows, which reads in Arabic, Wa-la galib illa Allah, meaning, “There is no greater conqueror than Allah.” This was the Nasrid motto, originated by Ibn al-Aḥmar or Muhammad I, the premier Nasrid ruler, who some believe is also the eponym of the Alhambra.

We proceeded onward to the Palacio de Comares, which consists of several rooms surrounding the Patio de los Arrayanes, so named for the hedges of myrtle on either side of the pond at the center of the courtyard. This is one of the more nondescript patios in the Alhambra. The white marble-tiled floors and the water in the pond reflect the light of the sun, creating a blinding effect – even while wearing sunglasses. This was not a design flaw, so explained Gosia. The Salón de los Embajadores (Hall of Ambassadors) sits at the north end of the patio within the Torre de Comares. This was the throne room, where the emir would officially greet his guests. As visitors made their way through the blinding Patio de los Arrayanes, upon entering the hall they would only be able to make out the silhouette of the emir, creating a sense of mystique and awe.

Speaking of awe, the ornamentation in the Salón de los Embajadores is reverential. The central chamber is perfectly square, with every surface of every wall covered in rich decoration. As in the Mexuar, the skirting board features colorful zellige tilework, which is met by two stories of masterful plasterwork detailed with arabesque, geometric, and epigraphic motifs. At the top of each wall is a set of five windows with filigree grills, letting in the subletest streams of light. The pièce de résistance is the ceiling – a dome composed of cedarwood panels depicting the Seven Heavens of the Islamic Paradise. The panels are decorated with interlacing patterns of celestial stars that appear pearlized in the glow of the light.

After gazing up at the ceiling for quite some time, Gosia summoned us to the portico just outside the hall, which consists of seven arches held up by columns with cubic capitals. She had us look closely at the capitals, each resting on a layer of zinc. The zinc serves as earthquake-proofing, as it helps to reduce the magnitude of a shockwave by absorbing the energy. Earthquakes have plagued the Granada basin for centuries, but the Nasrid engineers understood how to incorporate seismic-dampening materials in their designs, which is partially why the Alhambra has remained in such good condition for so many years. And, to this day, architects use similar techniques to earthquake-proof modern buildings.

We continued our tour in the Palacio de los Leones, the private chambers of the royal family, which was commissioned by Muhammad V in the mid-14th century and completed around 1390. The palace is so named for the fountain in its central courtyard, the Patio de los Leones, which features 12 marble lions holding up a gurgling basin. The mouth of each lion is jetted, shooting a stream of water into a channel that flows throughout the palace. Some believe the fountain was a gift or a remnant of Yusef ibn Naghrillah, the Jewish vizier of Granada in the mid-11th century, with the 12 lions representing the 12 tribes of Israel. Gosia had us approach two of the lions and pointed out a triangle on each forehead, which, she explained, may represent the two surviving tribes – Judah and Levi.

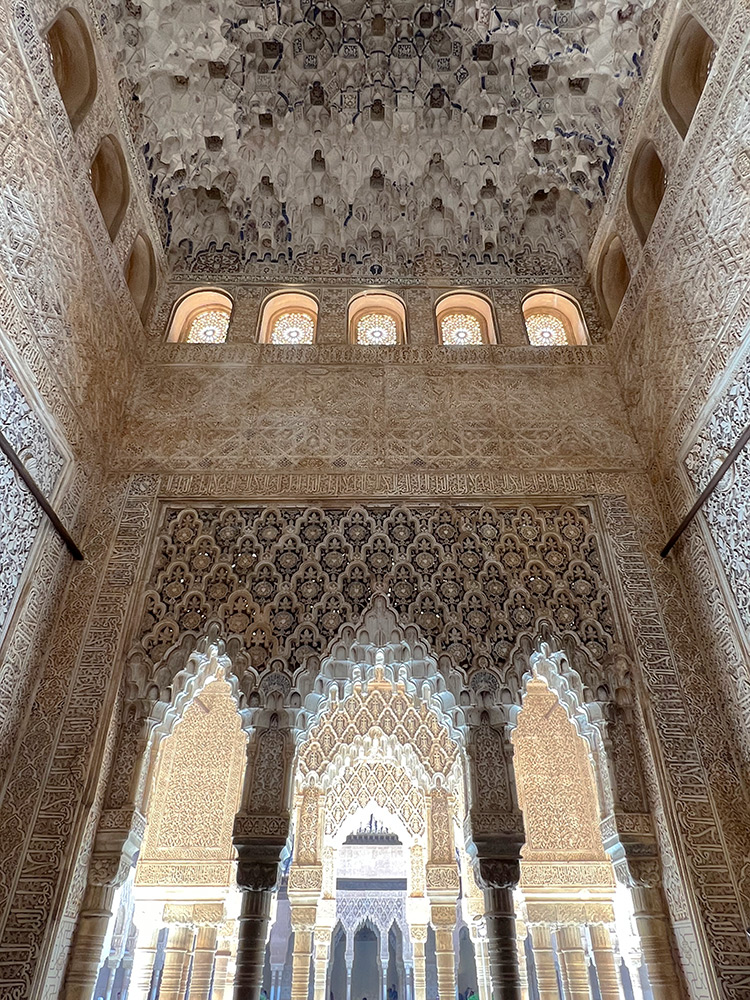

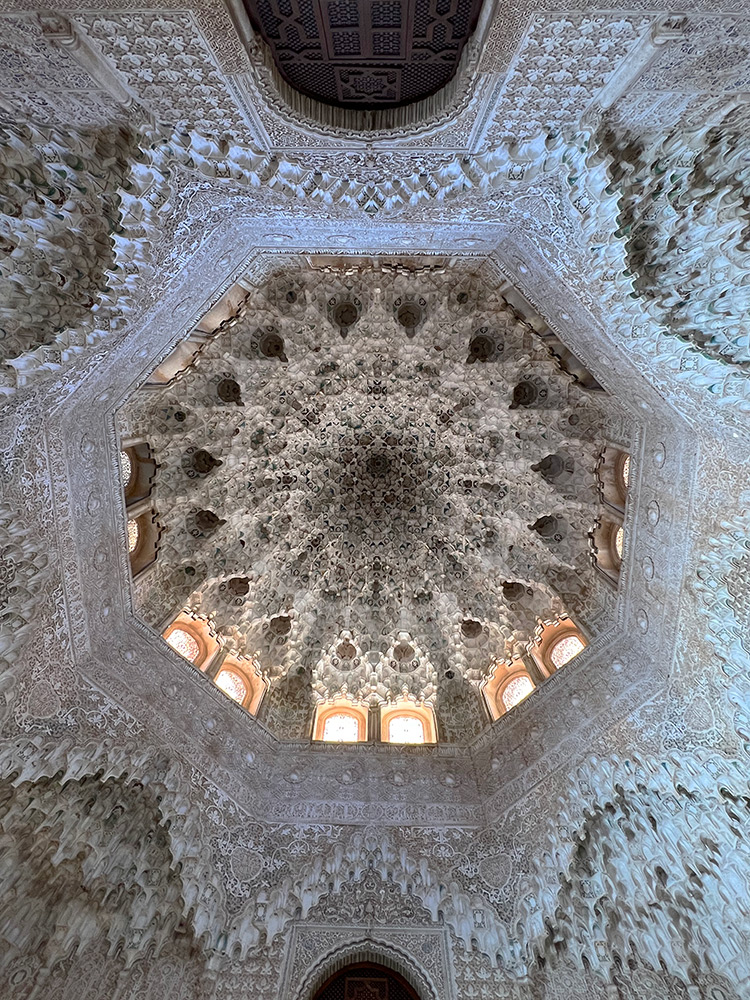

Surrounding the patio is a shaded colonnade and several porticos, all supported by magnificently adorned archways and columns. This design feature was most likely inspired by the Christian architecture of the time by way of Muhammad V’s close relationship with Peter the Cruel, the Castilian monarch. On the south side of the patio is the Sala de los Abencerrajes. It is said that after the Abencerrajes knight was discovered canoodling with Boabdil’s wife in the Generalife, the chiefs of the family were invited to the palace under the guise of a banquet – and beheaded in this room. To this day, a possible blood stain remains on the fountain in the center of the hall. In addition to this remarkable story, the Sala de los Abencerrajes is best known for its impressive domed ceiling, featuring an eight-pointed star composed of splendidly ornate mocárabe illuminated by 16 windows set just below the dome. It looks as though the ceiling is literally dripping with mocárabe stalactites. It took my breath away.

On the north side of the patio is the Sala de Dos Hermanas (Hall of Two Sisters), named for the two large slabs of marble that form part of the floor covering. This hall features several chambers and housed the sultana and her family. The central chamber also features a mocárabe-domed ceiling, which, would you believe, was even more stunning and perfect than the one we had just seen. This dome, composed of over 5,000 prismatic pieces, sits atop 16 miniature domes, forming what can be described as an exquisite flower. Sixteen arched windows allow the perfect amount of light to stream just beneath the apex, creating an effect of the most stunning three-dimensional spirograph. The walls leading up to the dome are covered in rich plasterwork, with the Nasrid motto, Wa-la galib illa Allah, repeated all around.

On the north side of the Sala de Dos Hermanas, Gosia had us peek into the Mirador de Daraxa, also known as the Mirador de Lindaraja. This small square chamber features three sets of double-arched windows overlooking the verdant Patio de Lindaraja – and is perhaps the most stunning room in all of the Alhambra. Covering the walls are pristine examples of all the design elements we had previously seen: zellige tilework, ornate vegetal and calligraphic plaster carvings, mocárabe valances above the windows, and a stunning vaulted ceiling. However, the ceiling was covered in an interlacing motif of vibrant stained glass. Historically, stained glass was used throughout the Alhambra, but this is the only place where it has survived. The late-afternoon sun set the ceiling aglow, creating rays of prismatic light that struck the walls of the chamber.

Our tour of the Alhambra had come to an end. Gosia led us through the Jardines del Partal, past ruins of former palaces, which are now surrounded by beautiful terraced gardens. We merged onto the Paseo de las Torres, which followed the eastern perimeter of the Alhambra ramparts and deposited us on to the Paseo de los Cipréses. We bid a gratitude-filled farewell to Gosia, made our way to the car, and began the 80-mile journey back to Málaga. Charles and I were both pooped, yet equally high on the elation effused from the incredible day we had just experienced. We drove off into the sunset, passing through the vega and the western mountains, leaving Granada and the Alhambra behind us. But it was just a farewell for now…as I know I will be back some day, to re-experience the magic of the city that lies at the foot of the snow-capped Sierra Nevadas in Al-Andalus.

Last visited in May, 2022